Welcome to our Magic artist interview series number #49!

This week we had the honour of meeting Dan Frazier over Skype and talk about his life and work.

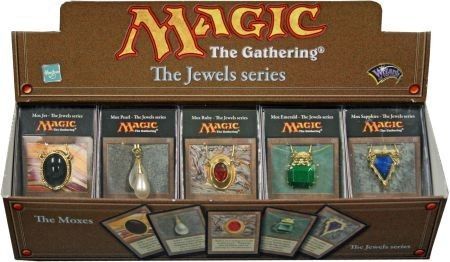

Dan was one of the original 25 Magic artists, where he painted the iconic Moxes, and more than 150 Magic cards since.

How did it start for you?

My mother gave me typing paper and I got to draw on it. I was never told not to, so I always did a lot of art.

Where did you grow up?

Littleton, Colorado. Rocky Mountains. When I moved there I thought it was going to be a cowboy town full of horses on the street and guys wearing cowboy hats, but… nope! It was just a regular old town.

Did you go to University there?

I went to the University of Colorado. I was reading Tolkien and drawing little cartoon guys like that, but I didn’t really know how to draw until my last semester.

“Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” taught me to see things like camera. This was a book by Betty Edwards, who was a terrible writer, but the exercises were really good. A camera doesn’t know anything about what it’s taking a picture of, but does a really good job taking at taking a picture, that’s what I had to learn how to do.

And I taught art for 20 years, so I would teach kids how to draw.

Did you develop your own work simultaneously to teaching?

No. I didn’t have a lot of time for my own work, you come home tired. I taught for 20 years then I retired and started doing illustration.

And did you develop a portfolio?

Well, when someone is paying you $15 a piece for ten drawings, they don’t care much about a portfolio, they just want it cheap. And then you learn, and you learn, and you learn.

When I was at GenCon I got introduced to the people at Wizards of the Coast. I did some black and white work for them and then they failed to pay me. Each month they would send me a message saying, ‘We owe you money’. Until they finally paid me. Now, nobody does that! Nobody says, ‘I owe you money’. They just write you off, but these guys didn’t.

Later on they had a new game and were looking for some artists, but they couldn’t pay much. They said, ‘Well, we want you to do these little tiny pictures the size of a playing card. Not the whole card, just half the card, and only on a box inside that half. Oh, and by the way, it has to be recognizable - not from here – from a couple feet away, and upside down. And it has to be full color’.

They were going to pay $100 a card, which is pretty good. They would pay $50 in cash, but the money wouldn’t come until they sold the product and got money coming in. The other $50 was in stock. Just stock… you know… that’s no good. But they would put our name on the cards, that’s nice! And we’ll have royalties, so I figured… 6% of nothing is still pretty good.

That turned out to be a game called Magic: The Gathering.

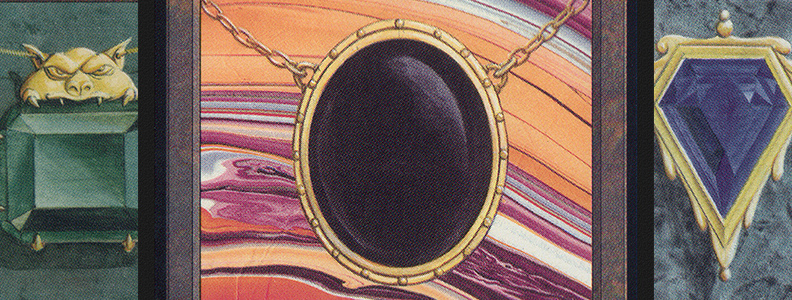

At that point there was an art director by the name of Jesper [Myrfors], and he would read the list of possible cards I wanted to do, so I was picking along. People have asked me why I picked the Moxes. There was this pearl thing, this sapphire thing, this ruby and this jet thing… so I thought, ‘Okay… Jewelry sounds easy”.

‘Okay, this thing is called a Mox Sapphire, Mox Ruby… But, what’s a Mox?’ and Jesper says, ‘Oh, we don’t know!’ [Laughs] So, in the beginning it was really pretty open, you could do anything you wanted.

So I did 18 cards and sent this stuff in, and Jesper called and asked if I could do some more. I ended up doing like 37 cards from the original Alpha set, which is probably more than anybody else did. That decision to do that turned out to be a really good one for me. Financially it was a pretty nice thing. Now, you’ve got to understand, this is not because of my skill, it’s because I got lucky. I’m not the most skilled artist out there but I am, by far, the luckiest artist.

I find your Moxes beautiful.

I disagree on that, but okay.

You don’t think so?

Oh no.. oh no!

What do you think about them?

They did what I was asked to do: you could recognize a Mox from across the room. I can hold one fifty feet away and you’ll go like, ‘That’s a mox!’. It’s simple, it can viewed upside down, it’s an icon, it’s like a stop sign. It’s not beautiful, it works. The reason it’s valuable is because of the rule that was put on it,and I had nothing to do with it. Because my name is on the card, I got famous!

Jesper did a great thing for all the artists out there when he insisted on the royalties and the names on the cards. Unlike, say, an artist at Disney. Who knows who is the artist doing all that work? You don’t.

At this point in time you had no idea what was going to happen with the game…

Oh, we knew exactly what was going to happen. It was going to be a game would be out there for a year and a half and then it would fail, and we would do something else. And I knew that I would never get paid for it and that the stock would be worth. So, the embarrassment of what I painted was not going to be seen by anybody, now that’s cool. [Smiles]

And when did you realize you were wrong?

I was at GenCon and I was talking to my wife on the phone, and she goes, ‘Honey, I’ve got a letter from Wizards of the Coast, it’s a royalty check’ I said, ‘What?! A royalty check?’, ‘Yes, it’s a royalty check for over four thousand dollars’. This is like free money! It’s like an uncle died and gave you some money, who would expect that? [Laughs]

I got really excited so I called up Jesper and said, ‘Hey! Jesper! I got a check for over four thousand dollars of royalties!” And he goes, ‘Yeah. Yeah, you did. But you know, someone’s going to make over ninety thousand dollars in royalties this year’. And I go, ‘Well, who?!’. And he says, ‘You! You dope!’ [Laughs]

The thing that really set it off: when I was at GenCon signing cards, a guy comes up and he sets down a stack of Mox Sapphires, about four inches tall, and there were ninety of them.

Jesus...

And so I sign the ninety sapphires. But he also had ninety ruby’s, and ninety pearls, and ninety jets. So that was pretty cool. But I still didn’t know this stuff was going to be really valuable, so I took the original paintings and I sold them for like $26 and $43.

That gotta hurt.

Oh no, no! It was great. Because I’m doing great, but somebody else is getting healthy too, and that’s good, to spread it around! I’m really lucky, might as well spread it around and let some other people have some fun too.

Do you know who you sold them to?

I followed them a little bit but I don’t pay much attention to it. I did know a fellow that has several of them.

Do you have an idea on how much they are worth today?

This fellow, his name is Josh, made a deal where there were three paintings, and mine was one of them. It was like a couple million dollars for them.

It’s interesting that the game got really big but the artists were able to partake on that success. I don’t know of many other games or many other products where so much of the success of the game flowed down to the artists that were putting it together, so that was an important thing to me.

So what happened after the release of the game?

My skills were not sufficient. If you take a look at the Jester’s Cap, it works, and its famous, but it wasn’t good enough. That’s when I started to take classes from this Italian fellow named Frank Covino, and I learned to paint the way the old masters painted. And that made a huge leap in my skills.

I did a painting of Richard Garfield and took it to a show, and some of the other artists saw it. They knew what I used to paint like, and when they saw this painting they did not smile and ask how I was doing, instead, they took me aside and said, ‘Okay. What happened? What did you do?’ I told them about this painting class with Frank Covino, and they got so enthusiastic about it that the next year they took the class with me. Frank Covino was happy to have all these professional artists in there, he was used to working with little old ladies doing pictures of their grandchildren.

Around what set this happen?

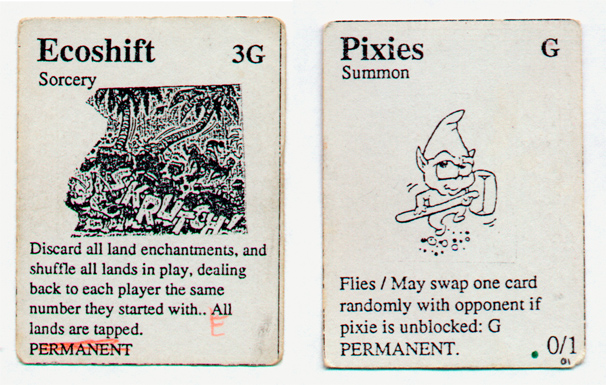

Around Unglued. I don’t know much about the game, but I did put my own deck together one time. You’ve got these blue decks, you have a goblin deck, and I had a ‘Frazier deck’. It was heavier on the black stuff.

Do you still have some of the originals?

I still have some, but most of them are gone.

Do you still follow the game?

Well, if you go to a convention, how do you make money? You got to pay for the room and the airplane and things like that, so I didn’t go to many conventions. But I finally got hooked up with my agent, and he showed me how to make money out of what I’m doing. Because of him I’m going to about six events a year, and he’s the one who brought in the idea of not signing cards for free.

You’re paying a lot of money to go somewhere, you’re taking a week out to go somewhere with all these expenses, and you’ve got to have some kind of money coming in. That allows me to go to some different conventions and provide a service for the people, doing the little alters on the cards and selling a few mats, makes it kinda fun.

I’ve been a lot of places. What it did was it allowed me to take my wife to all the various cities around Europe.

So would you say Magic changed your life completely?

Yes. My house is the house that Magic built.

Of the cards you made what are your favorites?

The Onslaught Swamp. It was one of the last ones I ever did for Magic, but it draws upon my skills that I learned about oil painting.

I really like Last-Ditch Effort, a bunch of goblins chasing up the hill.

What’s your least favorite?

Green Ward. I got in trouble with that one. I hated it so much that one time I was in Rome and this kid hands me the Green Ward, and I take it, tear it up and throw it over my shoulder. [Laughs] And I got in trouble for that.

I bet that was traumatic for him [Laughs]

I hate that card.

And what was the hardest card to paint?

There was an interesting one called Gustcloak Skirmisher. I have it here [grabs the painting and shows it to the camera]. The thing is, how do you paint a cloak of invisibility? [Laughs] Think about it! So that’s what we get paid to do. As an illustrator, you have a problem set in front of you, and you have to be able to solve it.

See, I don’t this kind of stuff anymore. The stuff I really like to do is… I’ll be right back [Grabs painting from the background]. It’s like this [Shows painting still in progress with a Dragon in the middle]. I can do that quicker than the old stuff I did for Magic.

Do you still paint often?

Yeah, I’m in my studio right now. [Points camera towards a painting]

This is the crazy thing: I know what my skill level is in painting. And I know that the reason people want me to sign their stuff has nothing to do with my skill level. I do not have a big ego involved in this thing. I know that I’m very lucky, and I got into it at the right time, made a couple of good decisions and it paid off big time for me. I’m very lucky, I cannot overstress that. But you can also make sure that when luck knocks at your door that you’re prepared.

If you’re a kid and you like art, you study and work hard, and you develop your skills to a really high degree, that assures you that you’re going to live a life of poverty in the future. It’s like learning how to play basketball: there’s only a couple of people that are going to make the big bucks. How many kids make money p ing basketball? You don’t. Being an artist is not one where you’re going to get rich at.

At least you can do what you love, that has value in itself.

Well, you got a point there, yes. And how lucky am I that I get to live in a nice place, and I get to draw dragons for a living? People pay me to do that! How crazy is that? I could get in trouble in highshool painting dragons, now I get payed for it.